For a swath of the world stretching from Sweden to Siberia; through the Baltics, Germany, and Poland; and across the Atlantic to Jewish delicatessens, rye bread carries meaning, memory, and history.

There are a dozen broad classes of rye breads, but dig deep into any region, and the subclasses grow and grow. To get a sense of how many regions turn to rye for their breads—and to begin to comprehend how many varieties of rye bread there are—head over to The Rye Baker and scroll through the categories on the right of the page.

I have brought Germans to tears with a taste of a German rye with so much “heimat” that their minds cross the ocean at first bite. I have also brought Danes to tears (of laughter) as I’ve tried to pronounce Rugbrød—my loaf is much more authentic than my pronunciation. In Finland, rye bread is so central to identity that in 2017 a national referendum elevated Finnish rye to the position of the country’s most national food. (Even in Finland, however, there are multiple types of rye bread.)

Try this thought experiment to get a sense of how much meaning a rye bread can hold. If given the choice of eating a warm, stacked pastrami sandwich, would you choose rye bread or Wonder Bread? If you are ready to go to the mat to defend a Jewish rye for that sandwich, then you are starting to get it.

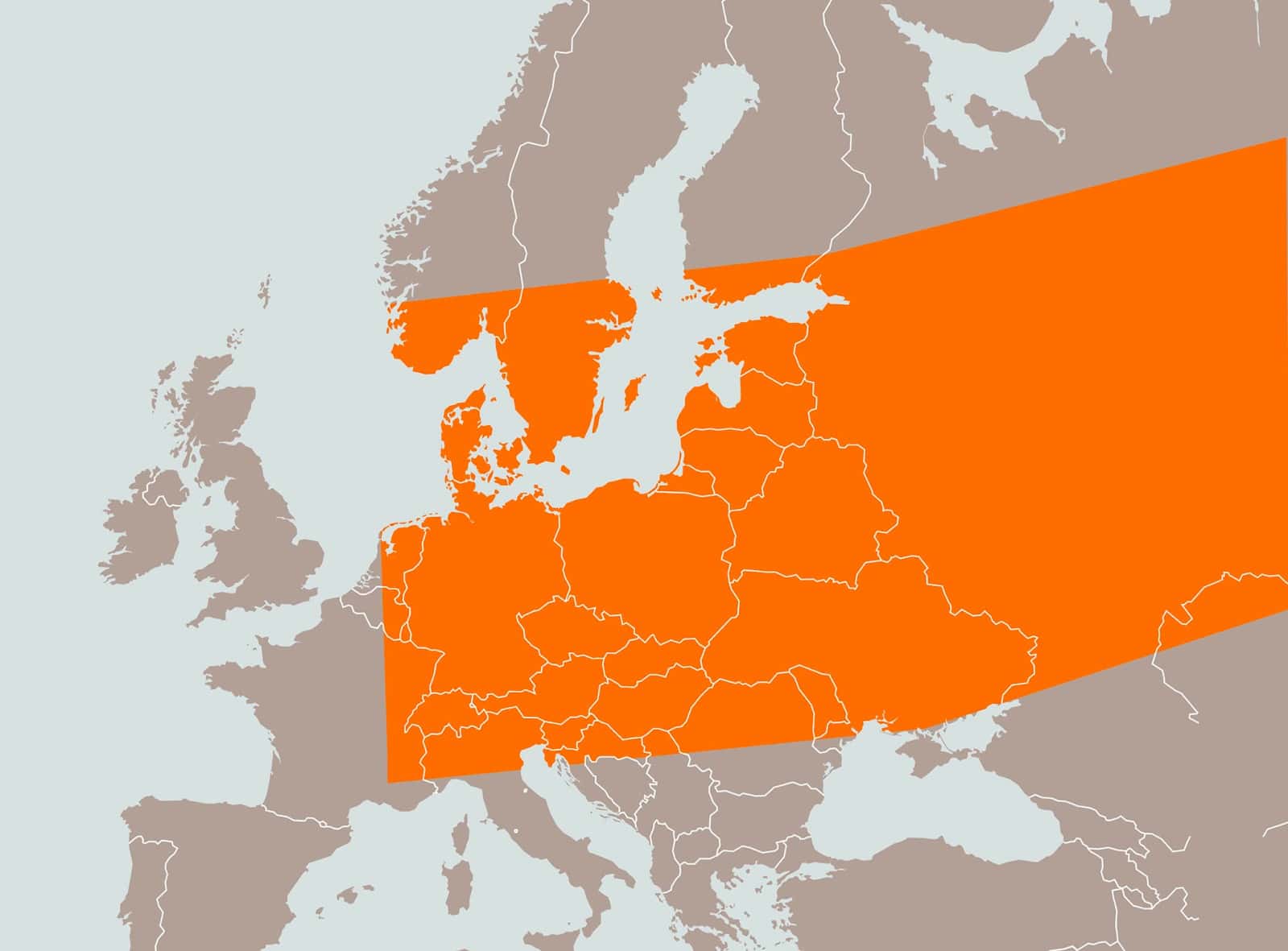

The Ecology of Rye Countries

One of the things I find most fascinating about food and culture is the interplay between geography and what people eat. For instance, wheat was first grown in the Middle East. Middle Easterners eat wheat bread: typically pita and other flat breads that can be baked in a tandoor-like oven. As wheat-growing spread, wheat breads developed to reflect local cultures: Armenian lavash, South Asian naan, Persian barbari, and what we now call Italian bread. (For more on the domestication of wheat and subsequent domestication of sourdough cultures to make wheat dough rise, you’ll need to borrow or buy a copy of Sourdough Culture: A History of Breadmaking from Ancient to Modern Bakers.)

Because of its plentiful and strong gluten content, wheat breads are light and airy, especially when compared to breads made of barley, rye, or oats. But wheat plants are priggish. They must have just the right amount of sunshine, warmth, and rainfall. If the climate is a shade too damp or too cool, your bread must be made from another grain.

Rye, in contrast, is as tough as the Vikings. According to the Handbook of Plant Breeding, rye can handle drought, sandy soil, acidic soil, or poorly prepared soil. Rye can be planted in the fall and it will happily survive the winter. Even if it is buried in snow for three months or more, it will lie dormant. As soon as the melt comes, it begin growing anew. In spring, rye’s green leaves are lucious and vibrant, offering hope on the horizon that there will be something new to eat besides a softening root vegetable from the cellar.

The dividing line between countries and cultures that eat wheat bread people who love rye is all a function of climate. Or, what the climate was historically.

Wheat Gluten vs. Rye Gluten

I have read about the biochemistry of rye breads a dozen times and it has never really sunk in. I just know that rye doughs are sticky, don’t rise well, and if they aren’t handled correctly, come out gummy. I’m using this opportunity to try once again to figure it out and then explain it in a way that I think will make sense to others. (I trust plenty of Maurizio’s dedicated readers will share thoughts on how well I’ve succeeded in the comments section. Rye elicits opinions!).

Wheat bread, naturally, is made from wheat flour, which has strong gluten. While gluten strength varies among varieties of wheat, when compared to rye, all wheat has stronger gluten than rye. Strong gluten networks in dough can be developed by kneading, stretching and folding, or a long autolyse. Wheat’s gluten becomes a tight, fibrous net that can stretch without tearing. Think of a window-pane test on your dough or a super-thinly stretched pizza crust as evidence. Carbon dioxide and water vapor produced by respiring yeast cells will be held in balloons of that gluten. Wheat bread rises as trapped gases fighting their way to rise into the atmosphere are thwarted inside gluten cells.

Rye flour has gluten, too. Enough that I have made more than one person with gluten intolerance sick after eating my rye breads. II won’t be running that experiment any longer.) Rye gluten is not strong enough, however, to hold dough aloft if it is inflated with carbon dioxide and water vapor by respiring yeast cells. What rye has instead of strong gluten to help it rise are starches that can be gelatinized. Gelatinized cells can hold gases and a rye bread can be leavened, but starchy gels are not nearly as elastic as those made of wheat gluten. The goal of rye bakers is to have those gels absorb a lot of water, forming a dense, mud-like ooze that can trap gases inside it. Keeping those starchy gels intact, though, is a tricky dance.

The first class of compounds to keep track of are called pentosans. If you can recall the formula for the basic sugar glucose (C6H12O6) you will notice that it is a ring with six carbon atoms (C6). Pentosans are five carbon carbohydrates (C5H8O4). Pentosans are plentiful in rye flour, and here is the part that matters to bakers: pentosans absorb water at more than 10 times their weight. Once dissolved they swell and vastly increase dough viscosity. Viscous dough is hard to shape, but it is a good thing to aim for in rye bread. All that cohesiveness is what allows rye doughs to rise. Gas bubbles can be trapped inside a dough rich in pentosans. Moreover, all that absorbed moisture keeps rye breads from becoming stale for days, and even weeks.

Biology of a Rye Seed

Manipulating rye flour to make a confident gel that will in turn make a rye bread with a proud, not gooey, crumb requires mastering embryology and then biochemistry. Hang with me. I’ll try to make this useful.

Look at the world through the lenses of a rye seedling. From the perspective of a seed, the introduction of water to a dry pellet of rye is a signal to get moving, and quickly. SPROUT!

Every grain of rye holds an embryo and a lunchbox packed with starch. Starch is useful for storing energy and a seed needs energy if it is to make shoots and leaves. The lunchbox is also filled with amylase enzymes (the same amylase enzymes found in diastatic malt, a common ingredient to help spur fermentation in bread dough). Amylase is a biochemical knife and fork: when it is wet, it cuts starches into smaller, bite-sized sugars. Even we humans can feel the jolt when we take in a mouthful of fine sugar.

When the temperature and moisture are right, rye embryos take off in the blink of an eye. Evolution favors seeds that break from the starting line the minute a warm rain signals the start of a race for growing space. The race is won by seeds that pull out their amylase and start breaking down starch at the first sign of moisture. A fast embryo that is sucking in sugars and putting its cell machinery to work will be the first to produce roots and shoots.

Rye flour is made by milling the seeds of rye plants. Rye flour, as you probably suspect, is full of starch. Amylase enzymes are also present, however, just as they were in seeds still on their stalks. The enzymes neither know nor care whether they are in a seed or in flour. The job of an amylase enzyme is to convert starch to sugar as soon as it is wet. When rye flour is hydrated, therefore, amylase enzymes break down starches because they are doing the job nature asked them to do.

However, while amylase activity is critical for seed growth, too much of a good thing can present problems in rye bread.

How to Bake a Tall Loaf of Rye Bread: Managing Starch Attack

In rye dough, a small amount of enzymatic activity—which turns starches into fermentable sugars—is a good thing. It results in a taller loaf and makes the bread taste sweet. If moistened rye flour is given too much time to ferment, however, amylase will degrade rye’s starches. The starch will not absorb water in the expected ratio. As a result, the bread’s interior will be excessively moist and gummy, sticking to the knife as it’s sliced. Additionally, the loaf will have a very dense crumb and typically a raised roof, also known as the dreaded “flying crust.” Sadly, there will be an air gap of an inch or more between a thin crust above and a paving stone below whose cement-like texture refuses to dry no matter how long it bakes.

The rye baker has to slow down the enzymatic destruction of starch in order to protect the future production of gelatins. Thankfully, there is an answer: impede the amylase by acidifying the dough and lowering its pH. The enhanced presence of hydrogen ions slows the enzymatic breakdown of starch by bending the tines and twisting the blade of amylase’s fork and knife. What is the best way to make acid? A very ripe sourdough starter and a large percentage of prefermented flour.

Here are the key points to baking a tall loaf of rye bread:

- Rye flour has low quantities of strong gluten but can stand tall if its pentosans are gelatinized.

- Avoid starch attack by deactivating rye flour’s amylase enzymes by lowering the dough’s pH before too much starch is degraded.

- Increased dough acidity also improves the swelling power of pentosans and increases dough viscosity, which aids loaf volume and helps to avoid an overly dense interior.

- Because of the acidifying benefits of sourdough, most traditional rye breads are made with sourdough as opposed to commercial yeast (though, sometimes also with instant yeast as a hybrid dough).

Why Rye Bread is So Good With Mix-ins

All that available fermentable sugar in rye flour consumed by sourdough yeasts and bacteria has important implications for bakers.

First, more available food for microbes means rye breads typically proof more quickly than sourdough wheat breads. Second, explosive microbial activity usually results in more flavor. Rye breads have high levels of sugar because the action of amylase enzyme converts starch to sugar. But it also has more sour flavors because a lot of sugar produces a lot of action from bacteria. Combining the acids produced by partying Lactobacilli and sugars generated by amylase enzymes and bread made only with rye flour, water, salt, and sourdough is going to be a cornucopia for the senses. It is starting to get clearer why northern Europeans in the rye belt are so passionate about their bread. Sometimes, they think, wheat bread is a little boring.

The combination of sweet and sour means that sourdough rye bread can be paired with a wide array of add-ins: coriander, fennel, cardamom, citrus, coffee, chernushka (nigella), cocoa, molasses, caramel, chocolate, cooked whole grains, sunflower seeds, flax seeds, pumpkin seeds, and of course, caraway.

Many Americans confuse the flavor of caraway with that of rye, and at the very least, many think that rye bread has to contain caraway seeds to be authentic. It isn’t totally clear why American rye breads contain so much caraway (please enlighten us if you think you know), but one version I’ve come across goes like this. In the colonial U.S., rye was a safety crop. You could rely on it surviving a cold New England winter. Breads known as “Rye and Indian” were often made with a mixture of rye, wheat, and corn flour depending on their availability. (See Sourdough Culture for a recipe for Rye and Indian and a fuller explanation of early American breadmaking.)

As Pennsylvania and then midwestern fields burgeoned, farming New England’s rocky and hilly fields became uneconomical. Pennsylvania and the Midwest are warmer and dryer than New England. Wheat does just fine there. As wheat production displaced rye production, the price of wheat undercut rye, which grew on far fewer acres. What we now think of as Jewish rye bread contained a higher and higher proportion of wheat flour. According to Amy Emberling, the rye baker at Zingerman’s, caraway was added to compensate for the relative blandness of white breads to palates accustomed to dark, dense ryes from the old country. The more wheat flour, the more caraway. Caraway rye, which is really overwhelmingly wheat bread, persists in the U.S. to this day.

In fact, we have our very own version of a sourdough Light Deli Rye with caraway (see above), and not because it wants for flavor—it has plenty of that—but because when used judiciously, caraway can enhance the overall flavor profile. Plus, it’s perfect for a pastrami sandwich.

Rye vs Wheat and Capitalism

Rye bread is hard to mechanize. The dough is sticky and heavy, making it difficult to knead and even harder to clean up after. Many rye breads are baked at low temperatures for long periods to provide time for moisture release. Even after they come from the oven, they should cool for at least a day before being sliced as additional moisture moves from the crumb through the crust. And as shown above, one of the best ways to inhibit starch attack in rye dough is the use of sourdough cultures. Sourdough is leisurely compared to yeast.

Everything about authentic rye bread is slow when compared to wheat bread. Wheat bread can be mixed in high-speed mixers, doped with large quantities of commercial yeast, and rammed through a continuous, high-temperature oven. Even cooling times are shorter for wheat bread than for rye. Turning out more bread in a shorter period of time is the key to selling more bread. There’s profit in speed.

To enjoy all the flavors of sourdough rye bread you will need to seek out bakeries in America doing it the old-fashioned way, or go to Europe and find an artisanal bakery with bakers still using their hands. Or, of course, make your own Rubgrod with a mix of rye and whole spelt flour with dark beer. Dark and rich, intended to be sliced thin for Danish smorrebrod (open-faced sandwiches).

Rye FAQs

What’s the difference between white rye, medium rye, and dark rye?

King Arthur Baking has an in-depth explainer on types of rye flour, but here is a summary. White rye flour (light rye), like white wheat flour, has had all of the germ and bran removed. Only the starchy endosperm of the rye kernel remains. Medium rye flour has some of the bran included. It is darker and more flavorful than white rye. Dark rye flour usually means whole grain rye: bran, germ, and endosperm are all there. But there is no standard classification, so some flours called dark rye have had some of their bran removed.

What is pumpernickel flour?

Pumpernickel is the real deal. Pumpernickel flour contains everything that was in rye seed: bran, germ, and endosperm. It is typically coarser than white or medium rye, darker in color, and very rich in flavor.

What’s Next?

If you want to dive into the world of rye, try your hand at our freeform Sourdough 90-Rye, which calls for 90% whole-grain rye, a ripe sourdough starter, and over 40% prefermented flour because, as you’ve just learned, we need to stave off that starch attack. The side effect? An incredibly rich, earthy, and knock-your-socks-off rye bread that’ll impress even your European neighbors.

Here is a dictionary of German bread names that covers the most general terms. Still, there are hundreds of species.

For the really dedicated, there is a whole lot more you could learn about the interplay of starch, enzymes, pH, acidity, water soluble vs. water insoluble pentosans, bacterial counts, ash content, salt concentration, dough temperature, falling numbers, flour extraction rates, amylograph tests, and the final goal of a dough viscosity that suits the bread you are trying to make. For the intrepid, here are two articles: Baking with Rye: The Devil is in the Chemistry and Assessment of the Starch-Amylolytic Complex of Rye Flours by Traditional Methods and Modern One.