The Summer, simultaneously one of my favorite times of the year (strawberries, blueberries, tomatoes!) and my most dreaded.

It's the time of year when temperatures kiss 100°F (37°C) here more days than I'd like to admit. As these blistering days set in, our baking slowly becomes unstable before we realize what's happening. This usually culminates in an over-proofed loaf, a nudge to exit complacency and elicits reflection. If you're like me, the idea—nay, the drive—to bake bread is still present even in the hottest part of summer, but even if we're lucky enough to have an air conditioner, we must adapt and learn how to bake sourdough bread in summer to avoid a sticky, run-away dough headed toward the land of the over-proofed.

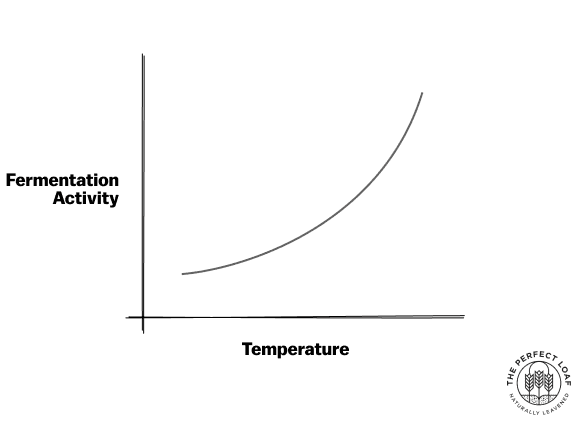

Temperature is a critical component of baking bread, and it's one of those factors (and more like an ingredient) that needs careful attention at each step. Temperature dictates the pace of fermentation as the bacterial and wild yeast which make up our sourdough starter change their metabolic activity depending on the temperature.

If temperatures in the kitchen and the dough are too low, fermentation is slowed dramatically. On the other hand, if the ambient temperature swings too high, it can mean a sourdough starter that's overly active, acidic, and needs refreshment earlier.

At a high level, the following are the first things I do when baking sourdough bread during the summer:

Next, let's look at each of them in detail. But why is it hard to bake bread during exceedingly warm temperatures?

If you're reading this post during the winter, see my post on baking in the cooler months →

Why is it hard to bake sourdough bread in the summer?

If you're a frequent reader here, you'll know how important dough temperature is and why we should pay attention to it during baking: temperature sets the stage for fermentation as warmer temperatures mean increased fermentation rates, and cooler temperatures mean a sluggish starter and likely final dough as well. During the summer, high temperatures will usually lead to sticky, excessively gassy, and eventually, over-proofed dough—sometimes without us even realizing why.

Further, all of the above is exacerbated if your recipe has high hydration, especially if you're working with a high percentage of whole grains or freshly milled flour.

What are the signs of over-proofed dough in the summer?

It might be odd, but the first place I look for when the dough gets close to over-proofing is the underside of the dough in the bulk fermentation when I dump it to divide. The dough will have an extremely porous look and sticky texture. It reminds me of those old-school natural bath sponges. So, when I dump my usual weekly sourdough bread recipe to begin dividing, if I see that texture, I know I need to step back, consult my notes, and check the time and temperatures.

Let's look at a roundup of signs that will help us diagnose an over-proofed dough.

Keep in mind that the following signs of over-proofing can also be related to other factors (such as high dough hydration, insufficient dough strength, or excessive enzymatic activity), but in general, here are some signs a dough might be over-proofed:

- excessively sticky dough during preshaping and shaping.

- excessively gassy dough at the end of bulk fermentation.

- a loose dough and sticky texture when shaping.

- excessive spreading when baking.

- lack of oven spring.

- a tight crumb (usually tight but still very porous—no dense spots).

- possibly an increased sour flavor.

Diagnosing an over-proofed dough can be challenging at times, and it's something we talk about oven over on our Discord channel for TPL Members. But using the cues listed above, it becomes a little easier to piece together the puzzle of determining when the dough is under or over-proofed.

How do I tell when my dough is sufficiently proofed in the summer?

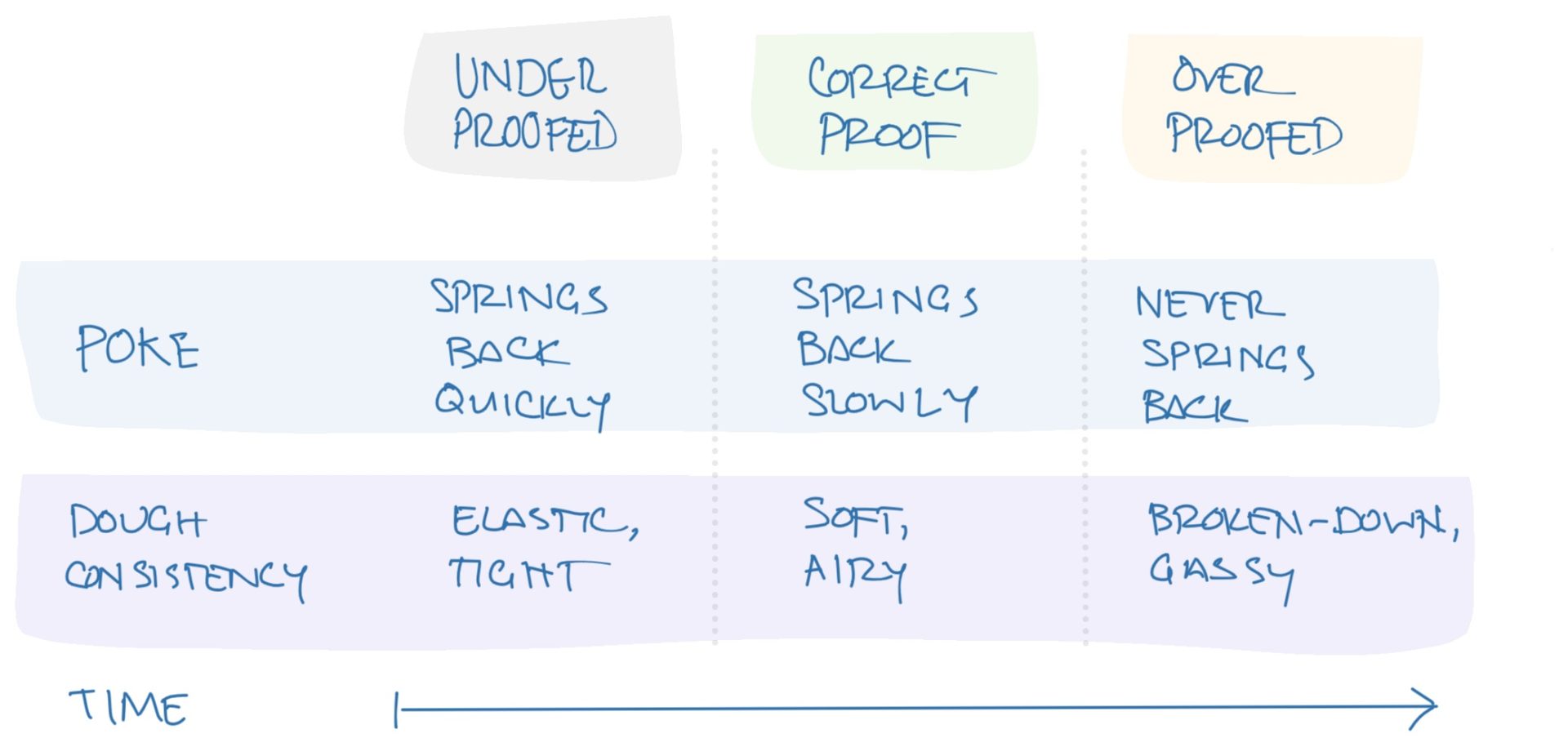

I always like to gently poke my dough in a few spots to try and determine its proof level. While the dough poke test is less accurate for cold-proofed doughs due to its tightening effect, it still gives you a good idea of how far along a dough is and when it needs to be baked. For the ambient-proofed (direct) dough, it becomes a much more reliable litmus test.

Poke the dough, and if the indentation:

- springs back very fast; it still needs time to proof

- slowly springs back; bake the dough soon

- stays depressed, bake immediately

You're looking for the dough to feel airy and light but still with a measure of elasticity and spring left in each poke.

As I mention in my guide to proofing bread dough, in the heat of the summer, I often like to err on the side of underproofing. Not a significant shift, mind you, but just a little earlier. When the dough gets into the oven and begins baking, it might be farther along than you think.

My top 3 tips to bake sourdough bread in summer

Once summer temperatures set in and I notice my dough fermenting faster or failing to rise in the oven as it once did in the cooler months, I'll focus on the following three things first.

1. Use ice-cold water when mixing

Using cold water during mixing is my number one method for combating the heat when baking sourdough bread in the summer. While this might seem an obvious first step, it's always my first approach to cooling my dough quickly. I keep a large bottle of water in the fridge and grab this when mixing.

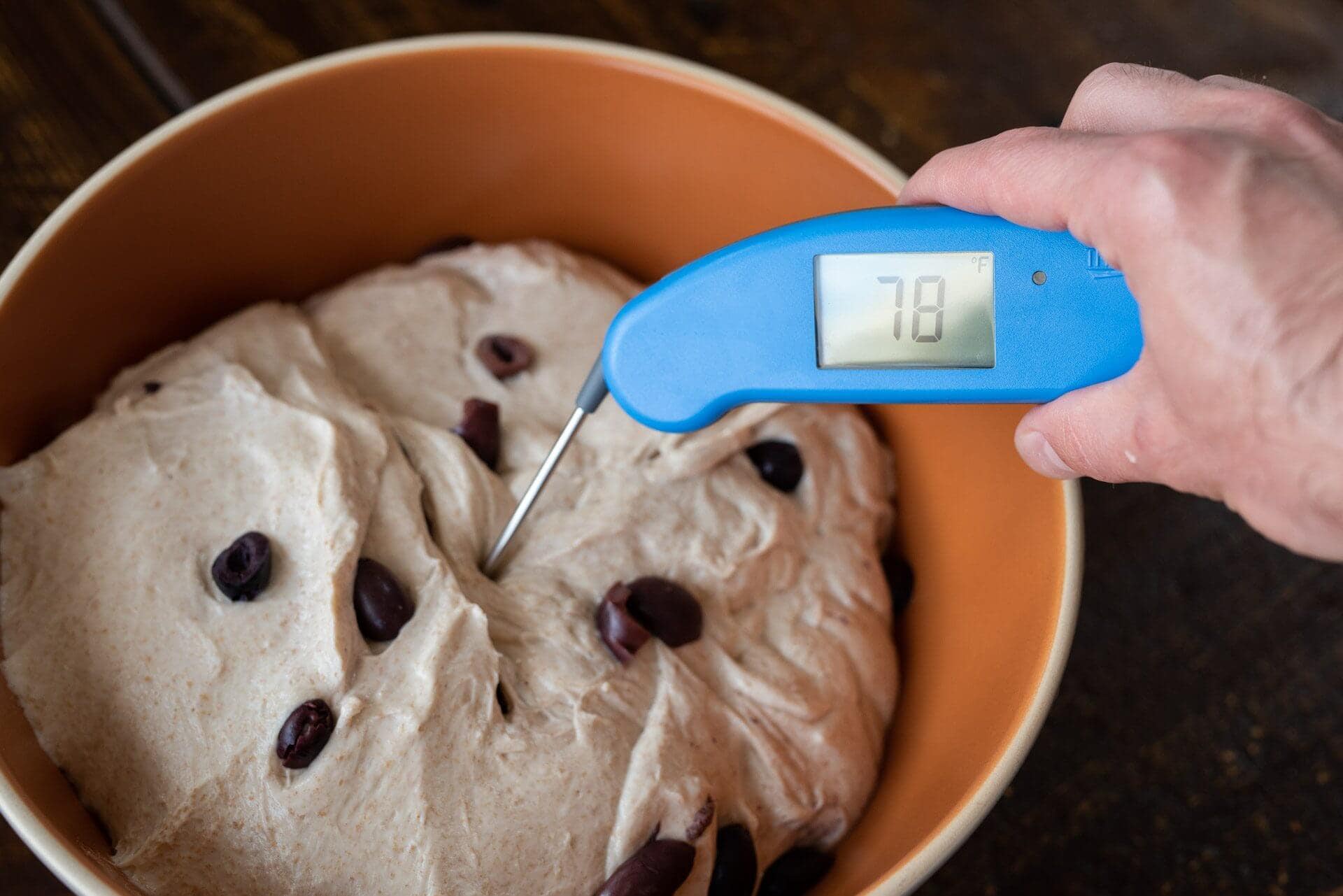

Pour some cold water into your mixing bowl when on the kitchen scale, then combine with some room temperature water until the temperature is a few degrees below your desired dough temperature (DDT). Remember that this water will have room-temperature flour added, but you also need to account for any increase in temperature from a mechanical mixer.

If your dough is set to spend significant time in autolyse, consider this time period: the dough will slowly warm if kept at warm room temperature during its rest, so cooler water might be called for.

Use cold water or even ice to cool your dough when mixing.

Keep a large bottle of water in the refrigerator and use it with ice to cool your dough to a few degrees below the desired dough temperature.

2. Keep sourdough starter mild and use before overly ripe

Keeping your sourdough starter mild and in control is of utmost importance in the summer. Fermentation is the cornerstone of great sourdough bread; it all begins with your sourdough starter.

In my experience, using a sourdough starter that's overly acidic means the dough will be extra active and, assuming other factors, can lead to a final loaf that's extra sour tasting with reduced leavening capacity. The greatest risk here, though, is that the dough will have too active of a fermentation rate and lead to overproofing.

Tips to keep sourdough starter mild

The following tips are a roundup of things I do during the summer to help combat warm temperatures in the order of preference.

- Switch to a clean jar more often. My starter jar gets inundated with excess starter, despite my best efforts to keep it clean. This “extra” starter ends up simply becoming carryover at each feeding.

- Reduce starter carryover. In the summer, my first approach to dealing with warmer temperatures is to reduce the starter I carryover to ensure it needs a refreshment only once every 12 hours. This might mean dropping my 20% carryover to as low as 2-5% (to total flour weight) in peak summer.

- Use cooler water. Similar to how using cooler water for your mixing can help, using cooler water to refresh your starter will slow its activity and buy you more time between feedings before it gets overly ripe.

- Reduce whole grain percentage. I will slowly back off the percentage of whole grains in my starter to reduce total acidity (keeping pH higher).

- Switch to a stiff starter. In my experience, a stiff starter is more resilient to warm temperatures. It has a wider window for ripeness and seems still usable, even if a little over-ripe. This is a drastic change, though, and is near the end of my solutions.

- Add a small percentage of salt to the starter. As a last option, you can use a very small amount of salt in each refreshment to help temper fermentation. I would start very low, perhaps at 0.5% to total flour, and work up to 1.5% salt (in my experience).

All of the above steps can help you keep your sourdough starter milder. Pick and choose the ones that align with your baking goals and help bring stability and control to your starter.

Keep your sourdough starter mild.

Pay attention to how your sourdough starter is ripening each day to keep it milder: refresh it more often, reduce the carryover percentage (seed or inoculation), use cool water, reduce whole grains, and even use salt in drastic cases.

Recommended reading: How I Feed My Sourdough Starter →

3. Reduce pre-fermented flour percentage

The amount of pre-fermented flour—typically a levain here on this site—is the jumping-off point for any recipe. It's the inoculant for dough, the small bit of yeast and bacteria added to raw flour and water to start fermentation. The larger the mass of this levain or sourdough starter, the faster the dough will ferment.

Think about it this way: the larger the preferment, the higher the number of yeast and bacteria microbes we add to our dough. The more microbes, the higher the fermentation rate.

Adjusting this part of the recipe does affect the formula you're following, though, and it should only be done after other measures have been attempted.

Reduce a recipe's pre-fermented flour percentage

To slow fermentation, reduce the pre-fermented flour in a recipe, effectively reducing the number of bacteria and yeast cells added to a dough.

Recommended reading: What's the Difference Between a Sourdough Starter and a Levain? →

A few more suggestions on how to bake sourdough bread in summer

Focus on the final dough temperature

Usually, you won't see drastic temperature swings from cool on one day to blazing hot on the next1. Much like the frog in a warming pot, the gradual shift from spring to summer doesn't seem to register with us as we bake day-to-day. The final dough temperature of our regular bakes starts to change a degree or two over a week, and slowly, the delta widens as outside temperatures increase.

Continuous monitoring of our dough is always the first step (you take your final dough temperature, right? 🙂). With continuous monitoring, you'll notice your FDT slowly creep upwards as the ambient temperature in your kitchen moves commensurately.

As the temperature hike inevitably sets in, counter it by using cooler water for mixing—that's always the first step. Next, let's look at that and a few more.

Recommended reading: An Introduction to Baker's Percentages →

Reduce dough hydration

Reducing the total dough hydration can help bring strength and stability to a dough, especially as temperatures (and humidity) increase. A dough that's overly wet and warm can quickly lose stability and become difficult to handle. In addition, more water might also mean increased fermentation activity.

I would start by dropping the dough hydration by 2%, increasing this percentage as necessary. For example, if a recipe calls for 76% water to total flour, drop this down to 74% and do a trial bake. Use baker's percentages to adjust your formula to ensure the recipe retains its original intention.

Put your bulk fermentation container in the refrigerator

To cool the dough at the end of mixing and before the first set of stretches and folds, place your covered bulk fermentation container into the refrigerator for 15 to 30 minutes. This isn't enough time to fully chill the dough, but it's enough to cool the container and take the edge off.

Be sure to keep an eye on the dough, so it doesn't go in the other direction and dramatically cool. The time in the refrigerator depends on your bulk fermentation container: it might take longer to cool if it has high insulating properties or a short period if it's thin-walled (such as a plastic tub). For example, the thick ceramic bowl I typically proof my dough inside can easily handle a 30-minute chill before the dough temperature inside drops drastically.

Watch the work surface temperature

When I mix by hand, I typically slap and fold (knead) my dough for several minutes at the end of incorporating all the ingredients. Because this technique involves working the dough on a work surface (my kitchen counter), keep an eye on the temperature of the surface itself. We can't easily change our work surface temperature up or down, but if you expect to have several minutes of work surface contact, cool the mixing water a little more than usual to offset any expected warming.

General suggestions when baking in the heat of the summer

A few last tips for baking sourdough bread in the summer:

- Be sure to store your flour properly when it's warm in the kitchen. Keeping your flour, especially whole grain flour, cool in the freezer can help prolong its lifespan.

- Watch where you place your dough during bulk fermentation: near a window that gets overly warm or under an air conditioner vent can have adverse (or desired) effects on the dough.

How to bake sourdough bread in summer FAQ

Why does my dough feel sticky in the summer?

It might ferment faster than expected due to increased ambient and final dough temperatures.

Why does my dough overproof in the summer?

Warmer temperatures mean increased bacteria and yeast fermentation activity. With sourdough, an excessively acidic dough resulting from increased fermentation will degrade gluten structure and lead to more spreading in the oven, less rise, and a potentially more sour flavor.

What's next?

Given that it's likely quite warm in your location as you're reading this, perhaps a quick sourdough galette with peaches and blueberries is in order. Or an easy no-knead sourdough bread that requires little but results in a lot?

Is there anything I missed in this how-to bake sourdough bread in summer guide? Also, if you have a burning (😅) question about baking in the summer that I didn't address in this guide on how to bake sourdough bread in the summer, please leave a comment below!

Although, here in the Southwest of the USA, night temperatures are usually very cool with scorching day temperatures.↩